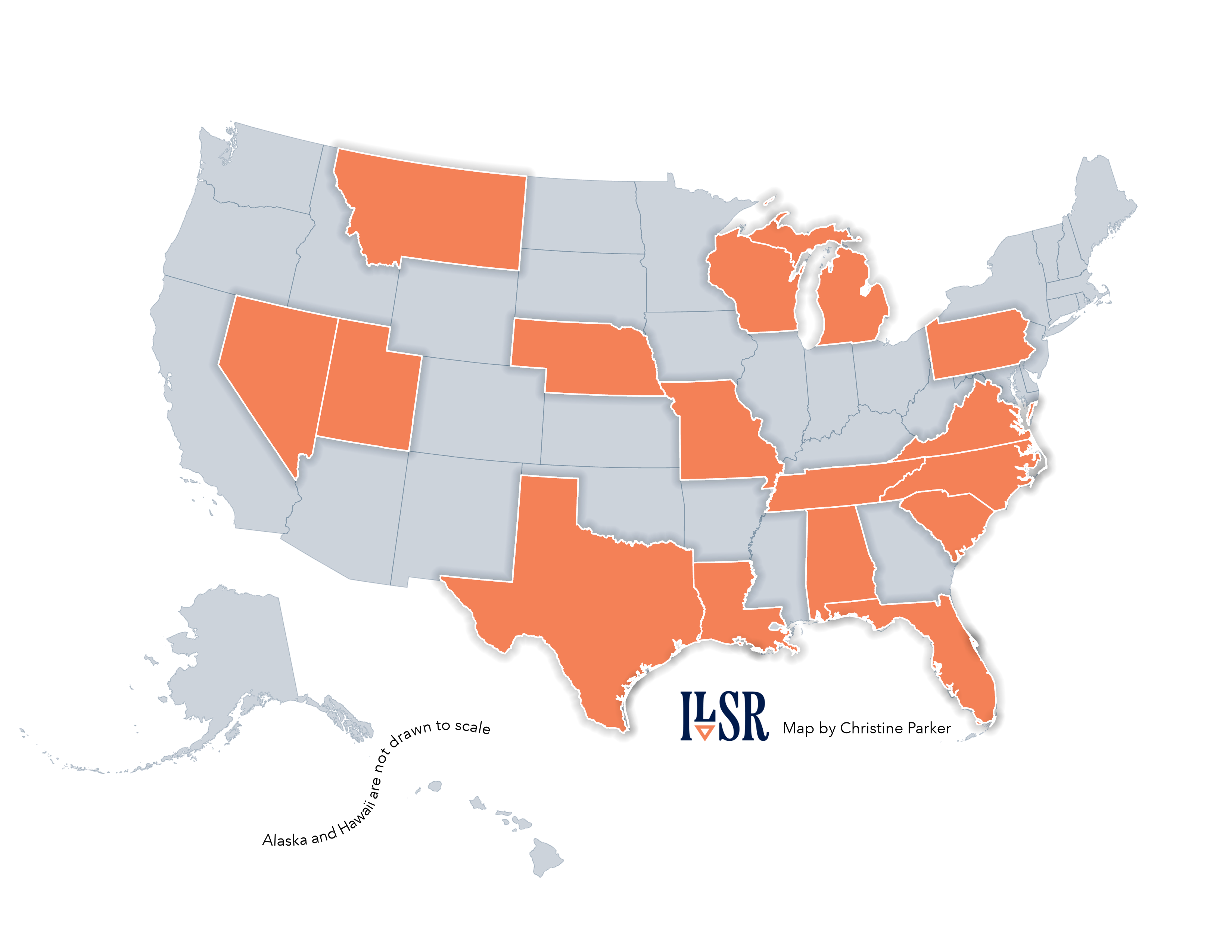

As the federal government makes unprecedented investments to expand high-speed access to the Internet, unbeknownst to most outside the broadband industry is that nearly a third of the states in the U.S. have preemption laws in place that either prevent or restrict local municipalities from building and operating publicly-owned, locally-controlled networks.

Currently, there are 16 states across the U.S. (listed below) with these monopoly-protecting, anti-competition preemption laws in place.

These states maintain these laws, despite the fact that wherever municipal broadband networks or other forms of community-owned networks operate, the service they deliver residents and businesses almost always offers faster connection speeds, more reliable service, and lower prices.

In numerous cases, municipal broadband networks are able to provide low-cost or free service to low-income households even in the absence of the now expired federal Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP). And for several years in a row now, municipal networks consistently rank higher in terms of consumer satisfaction and performance in comparison to the big monopoly Internet service providers, as PCMag and Consumer Reports have documented time and time again.

Nevertheless, these preemption laws remain in 16 states, enacted at the behest of Big Cable and Telecom lobbyists, many of whom have ghost written the statutes, in an effort to protect ISP monopolies from competition.

The Infrastructure Law Was Supposed to Move the Preemption Needle But …

In March of 2021, President Biden first issued his vision for a bipartisan infrastructure bill – which would eventually include $65 billion for broadband expansion with $42.5 billion of that earmarked for building new networks under the BEAD program. The President wanted to center nonprofit municipal and cooperative business models in his plan to connect unserved and underserved communities, while bringing competition to a broken market that has left Americans paying among the highest prices for high-speed Internet service of any developed nation in the world.

The Biden-Harris administration’s “American Jobs Plan” called for broadband investments and policies that would “promote price transparency and competition among Internet providers, including by lifting barriers that prevent municipally-owned or affiliated providers and rural electric co-ops from competing on an even playing field with private providers.”

The President’s call to action also envisioned an infrastructure bill that would “prioritize support for broadband networks owned, operated by, or affiliated with local governments, non-profits, and co-operatives – providers with less pressure to turn profits and with a commitment to serving entire communities.”

Ultimately, however, when the Congressional sausage-making was complete and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) was passed in November 2021, the bill deemphasized the Biden-Harris administration’s community-centered, local choice approach.

Still, it should be noted that the seed of the Biden-Harris administration’s vision did make it into the law, as the law specifically says any state that uses BEAD funds to build new networks must “ensure the participation of non-traditional broadband providers (such as municipalities or political subdivisions, cooperatives, non-profits, Tribal Governments, and utilities).”

Yet, neither Congress nor the NTIA – the agency charged with overseeing the distribution of the funds – has enforced the letter of the law. Instead, even those states that did not lift “barriers that prevent municipally-owned or affiliated providers and rural electric co-ops from competing” are still receiving their share of BEAD funds, all but ensuring the lion’s share of BEAD funds in those states will go to the big monopoly providers.

Pandemic Triggers Preemption Roll Back

But even without the federal government compelling states to remove preemption laws, the Covid-19 pandemic that shut down the nation in March 2020 was enough to convince four states that the preemption laws they had on the books were counterproductive, especially in the midst of a remote work and schooling boom, and as more and more commerce and governmental services moved online.

In 2021, Arkansas and Washington passed legislation significantly rolling back legislative barriers on publicly owned broadband networks. In 2023, Colorado rolled back a law that required communities to hold a referendum vote to opt out of a state ban on municipal broadband. That law was repealed after over 120 communities across the state overwhelmingly voted to opt out of the state preemption law, fueled no doubt by the success of the municipal networks in Estes Park, Fort Collins, and Loveland. In May of 2024, Minnesota followed suit, rolling back its preemptions laws.

Having tracked community broadband networks across the nation for nearly two decades now, we believe that locally-rooted, democratically-accountable networks are the best path for long term success.

Furthermore, we believe community-led broadband is the best option for promoting economic prosperity, improving quality of life, and ensuring broadband access for everyone irrespective of income and background.

Therefore we support legislative efforts to remove the preemption barriers that remain.

The 16 States That Still Have Preemption Laws Limiting Community Networks

Below is a list (and explanation) of the 16 states that still have preemption laws on the books that either outright prohibit or erect severe barriers to building and operating publicly-owned, locally controlled broadband networks.

Alabama: Municipalities are allowed to provide telecommunications services but state preemption laws impose numerous restrictions that all together make it extremely difficult for municipalities to build and operate a broadband network.

Alabama limits networks to community boundaries, preventing Opelika from expanding to serve others in the region, bringing opportunity to more and allowing its fixed costs to be spread among more subscribers.

As an example, Alabama prohibits municipalities from using local tax dollars or other funds to pay for the start-up expenses that any capital intensive project like network construction requires.

The law also requires municipal broadband projects to cover ongoing expenses and debt service from network revenues alone, which like any business may take years to reach; to say nothing of the fact that it forecloses the option of local communities deciding that the service is so valuable that it’s worth being subsidized by the local government, as is done with other basic infrastructure such as roads and schools. Statute.

Florida: Imposes numerous restrictions that have scared local governments away from investments though they likely could have navigated them. The state imposes taxes on municipal telecommunications that do not apply to other municipal services.

Communities considering an investment must conduct public hearings under specific circumstances and prepare a report showing “a plan to ensure that revenues exceed operating expenses and payment of principal and interest on debt within four years.”

Not all business models will break even in that time - especially when the networks are often focused explicitly on low-income neighborhoods that have been left behind. Statute.

Louisiana: Has among the strongest prohibitions that were made stronger after Lafayette launched LUS Fiber.

Municipalities must hold a referendum and are required to “impute” (or invent) additional costs that would apply to a private provider if it were offering services.

This requirement invites endless litigation as there are no agreed-upon standards for what these fees could be.

A community that somehow surmounts these obstacles would then lose the ability to charge franchise fees and similar obligations to other operators in the community – though those fees are usually owed to the public as compensation for using the community rights-of-way for poles, conduits, etc. Statute.

Michigan: Requires public entities to issue an RFP and can only proceed with a public investment if they receive “less than 3 qualified bids from private providers.”

They are also required to subject themselves to the same terms and conditions as those specified in their request for proposals - which is code for having to combine all the limitations of a public entity with the limitations of a private entity and the benefits of neither. Local governments are limited in serving any areas outside their boundaries. Statute.

Missouri: Limits municipalities and public power systems from telecommunications services leasing and selling for non-internal purposes but exempts “Internet-type” services.

What that means currently may be arguable but several communities have built fiber networks to offer Internet access to the public for a fee. Statute.

Counterintuitively, KC Fiber, a municipal network in North Kansas City, offers every resident within city limits fiber Internet service for free.

Montana: Local governments can invest in networks only if such services are not available from a private provider.

“An agency or political subdivision may act as an internet services provider when providing advanced services that are not otherwise available from a private internet services provider within the jurisdiction served by the agency or political subdivision.”

Like Pennsylvania, a service may be available to a few addresses at exorbitant prices and a community would not be able to move forward with a project. Statute.

Nebraska: Has among the worst prohibitions of municipal networks. The relevant law states:

“An agency or political subdivision of the state that is not a public power supplier shall not provide on a retail or wholesale basis any broadband services, Internet services, telecommunications services, or video services.”

Dark fiber, which is almost never regulated or limited even in states that limit municipal broadband, is also effectively prohibited due to complicated restrictions meant to protect the big telephone monopoly – CenturyLink/Lumen.

However, Lincoln recognized it could lease conduit and has built an impressive network doing just that.

Nevada: Prohibits municipalities with populations of 25,000 or more and counties with populations of 55,000 or more from providing telecommunications services. Statute. Statute.

Small wonder then, that the Silver State is a virtual community broadband desert with the notable exception of Churchill County Communications, a telephone cooperative first established in 1889.

North Carolina: Imposes numerous restrictions on community-owned broadband that have the practical effect of severely curtailing any such effort.

For example, as explained by the prominent telecom attorneys Jim Baller, Sean Stokes, and Casey Lide, “public entities are required to comply with unspecified legal requirements that may apply to private providers; impute phantom costs into their rates; conduct a referendum before providing service; forego popular financing mechanisms; refrain from using typical industry pricing mechanisms; and make their commercially sensitive information available to their incumbent competitors.”

No new municipal networks have been built since the law took effect, though Wilson’s Greenlight Network has still been able to thrive as one of the best examples of municipal broadband in the nation. North Carolina’s limits only apply to networks that would charge a fee for service. Statute.

Pennsylvania: Local governments are required to get permission from the local telephone company prior to investing in a network or partnership. This is literally the language of the statute:

“A political subdivision may offer advanced or broadband services if the political subdivision has submitted a written request for the deployment of such service to the local exchange telecommunications company serving the area and, within two months of receipt of the request, the local exchange telecommunications company or one of its affiliates has not agreed to provide the data speeds requested. If the local exchange telecommunications company or one of its affiliates agrees to provide the data speeds requested, then it must do so within 14 months of receipt of the request.”

Communities cannot consider factors such as whether the incumbent service is affordable, available to everyone, or reliable.

South Carolina: Effectively prohibits municipal networks by requiring them to invent phantom fees that would be applicable to private service providers – which would be subject to endless litigation. As with some other states, community providers would have to include unnecessary fees into their services to make them less competitive. Statute.

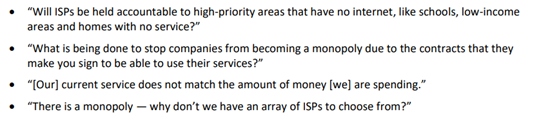

When state broadband officials conducted “listening tours” across the state to compile its Five Year Action Plan to qualify for BEAD funding the plan cited widespread criticism of monopoly ISPs.

The plan also explictly acknowledged the state’s preemption law was a stumbling block to maximizing its effort to provide universal connectivity.

The plan listed the three most common complaints they heard from residents:

“1) ISPs are not interested in expanding Internet service if it is not profitable, which can result in lack of access or spotty service in an area; 2) that ISPs are creating monopolies and customers are beholden to the prices and services they offer, regardless of the quality of services; and 3) that ISPs are difficult to contact, are not helpful with repairs and provide confusing information about service offerings and costs.”

Because of the state’s preemption law, South Carolina’s BEAD plan concluded: “no government entity has chosen to make a filing at the Public Service Commission of South Carolina to declare an area is unserved and that the government entity seeks to provide retail Internet service in that unserved area,” adding how the South Carolina Broadband Office “may raise any concerns for the consideration of the State General Assembly.”

Those concerns were either never raised or put on the back-burner as South Carolina’s preemption laws remain in place.

Tennessee: Municipal broadband networks are only allowed in communities with an existing municipally-owned electric utility.

And even then, those municipalities are only allowed to offer broadband service to households and businesses in their service territory.

It’s important to note, however, that even with Tennessee’s preemption law, the state is home to one of the most celebrated municipal networks in the nation, EPB Fiber in Chattanooga. And in Knoxville, the city's electric utility is currently building what will be the biggest municipally-owned network in the U.S. (KUB Fiber) when it is completed.

Texas: Home-rule cities can build and operate Internet access networks, but only to offer “data services” because the state outlaws municipal telecommunications services directly or indirectly. Mont Belvieu was able to clarify this interpretation of Texas law prior to building its network. Statute.

The municipal network in Pharr has distinguished itself among the handful of municipal networks in Texas in a city that was once considered one of the worst connected cities in the nation.

And like a number of other municipal networks, Pharr is offering low-cost high-quality 500 Megabit per second service for just $25/month and for qualified low-income households with a school-aged child in the home, gig-speed service is offered at no cost.

Utah: Effectively prohibits offering municipal Internet service as a retail operation but allows wholesale-only business models. As a result, most of the municipal networks we see in Utah use the open access business model, though Spanish Fork has a thriving retail network that predates the restrictive law.

In 2013, Utah restricted municipal bonds relating to telecommunications. Wholesale-only statute; Bond limitation statute.

Virginia: Allows only municipal electric utilities to offer broadband service but not any form of cable TV service.

State law also prohibits municipal providers from subsidizing any of its broadband services and requires them to charge rates in line with private sector costs, effectively preventing publicly-owned network providers from offering even low-cost service to low-income households that is less than what private incumbent providers offer.

Additionally, municipal providers must “comply with numerous procedural, financing, reporting and other requirements that do not apply to the private sector,” as noted by Baller, Stokes, and Lide. Many community networks in Virginia are organized as Wireless Service Authorities.

Wisconsin: Requires specific local hearings and feasibility studies and that prices are greater than “total service long-run incremental cost” that includes phantom costs that are similar to those incurred by a non-governmental utility.

Such requirements are subject to endless litigation because there is no agreed-upon way to define these costs. Statute.

(*Our list borrows heavily on the legal research of longtime telecom attorneys Jim Baller, Sean Stokes and Casey Lide of Keller & Heckman and the work of the Coalition for Local Internet Choice (CLIC). Their list, which hasn’t been updated since 2021, can be found here.)

Inline image of U.S. Capitol building courtesy of rawpixel.com/CarolMHighsmith via CC0 1.0 Universal

Inline image of Opelika City Hall courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Inline image of LUS Fiber logo on stadium scoreboard courtesy of LUS Fiber Facebook page

Inline image of no wifi courtesy of Paille, Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic

Inline image of Knoxville Sunsphere courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic

Inline image of Virginia welcome sign courtesy of Jimmy Emerson, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic