Fast, affordable Internet access for all.

Portland activists are renewing their calls to prioritize the construction of a municipally owned broadband network in the Oregon city of 635,000. With an historic infusion of federal subsidies and a looming shakeup of city politics, advocates for community-owned broadband say the time is right to finally revolutionize city telecom infrastructure with an eye on affordability.

“Ten years ago was a perfect time to embrace community broadband and nothing has changed,” Russell Senior, President of Personal Telco, a nonprofit wireless network, and Municipal Broadband PDX, a nonprofit advocating for publicly-owned fiber networks in Multnomah County, Oregon told ILSR.

“ISPs continue to exercise monopoly power and have their boot on the neck of subscribers,” he said. “The most practical and effective way to get out from under that boot, in light of persistent federal complicity, is local public ownership of the infrastructure that gives them that power.”

Portland has historically been at the very center of the debate over monopoly power and competitive broadband access, and city officials have been contemplating a publicly-owned broadband network for more than 20 years. It’s a concept other Oregon cities, like nearby Hillsboro, adopted years earlier.

But despite widespread public support for such a network in Portland, the effort has struggled to gain political traction. But thanks to a recent voter-approved restructuring of Portland's entire city governance that will dramatically expand the number of electable representatives, activists believe there’s a renewed opportunity for reform.

“We currently have a weird commission form of city government, where 5 people–a mayor and four councilors–all participate in both legislative and executive functions,” Senior said. “Of the five members, the mayor is silently hostile, and only one commissioner, Carmen Rubio, seems to get it.”

The changes to the Portland City Government Charter mean that starting in 2024, the city will switch from five citywide council seats to four districts, each represented by three City Council members. Those new members, to be chosen via ranked choice voting in the November 2024 elections, should create a new opportunity for education and reform.

“The change in the Portland city government charter means all the newly created council seats are up for election and creates an unprecedented opportunity to influence how fast-Internet service is provided in the Portland Metropolitan region,” the Electronic Freedom Foundation (EFF) notes in a blog post.

“There is some hope that in the lead up to the new City councilor elections that a combination of candidate and voter education and public pressure can motivate more serious action,” Senior said.

A History Of Local Activism

Municipal Broadband PDX was created in 2018 out of frustration at the high prices, slow speeds, and substandard customer service inherent in the broadband offerings of the city’s regional duopoly: Comcast and CenturyLink (now Lumen).

In 2019, the group spearheaded city efforts to conduct a $225,000 feasibility study to determine what it would take to deliver a fiber network capable of delivering affordable, next-generation access to all 815,000 residents living in Multnomah County.

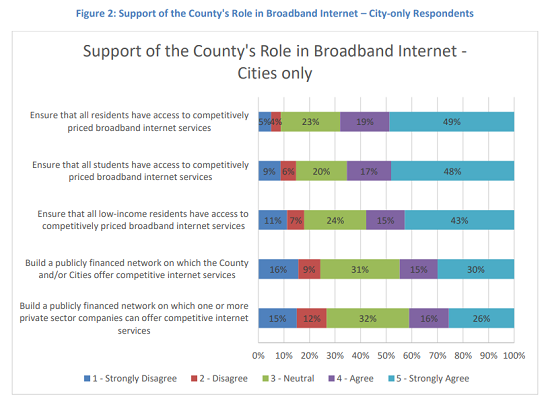

That study, conducted by CTC Technology & Energy, found that six out of ten residents felt that regional broadband giants had failed to deliver affordable, uniform broadband access. It also estimated that it would cost somewhere around $1 billion to pass every location in the county–with profitability achieved by a 36 percent take rate.

“The financial analysis developed for this report suggests that the countywide strategy would be self-sustaining at a take-rate of 36 percent, assuming a 4 percent bond interest rate and residential service fees of $80 per month,” the study found.

A Portland-only network would obviously be far less expensive. Despite this, reformers say progress on these efforts has routinely failed to materialize, most commonly thanks to the political stranglehold entrenched telecom monopolies have over policymakers on the city, county, state, and federal level.

“In our community, we all pay something like $500 million per year to the incumbents, and our elected leaders pretend to be frightened of a $900 million investment where we own instead of rent, and enjoy the full benefits of ownership,” - Russell Senior

Portland is already home to a publicly-owned dark fiber network used for essential city services known as IRNE (Integrated Regional Network Enterprise) Net. The EFF and other activists argue it makes sense to expand access to that network to all city residents with an eye on affordability, uniform access, consumer privacy, and transparency.

“Expanding and opening access to IRNE Net would encourage the growth of new local ISPs, provide a new source of revenue for the City of Portland, and create the means through which to give Portlanders affordable access to high-speed internet, in every home and business,” the EFF said.

Both the EFF and Municipal Broadband PDX point to a recent Harvard Study showing that municipally owned and operated broadband networks tend to offer service that’s faster, less expensive, and more transparently priced than traditional private sector offerings. Owned and staffed by locals, such networks also tend to be more accountable to the public.

Both organizations say that city residents should contact them if they’re looking to volunteer their time toward the goal of affordable, uniform access citywide.

“Residents need to start now to educate the new City Council representatives on how to change the way of doing business in city government,” the EFF said. “It is possible to reclaim power from the Big Tech Internet providers in Portland, and offer truly fast, affordable [I]internet service to every Portland home and business.”

Broader State Efforts

The revitalized effort to bring affordable access to Portland comes as the state is also pondering how to best spend an historic infusion of federal broadband grants made possible by both Coronavirus relief and infrastructure legislation.

While Oregon received $157 million in American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds, it wasn’t used to meaningfully challenge the monopoly power at the heart of unaffordable broadband access, Senior said.

“The city burned most of their ARPA funds doing short term things like handing out Chromebooks and cellphone company hotspots,” he said.

Senior, like many broadband activists, said he’s been frustrated by the ambiguous rhetoric local Portland and Multnomah County politicians use to obfuscate the real cause of spotty and expensive broadband access: competition-eroding telecom monopoly power.

“To me, framing the problem as a ‘digital divide’ is a way to distract from the fundamental problem, to delay action where it would do the most good,” he said.

“Controlling costs through public ownership is really the only way of solving the digital divide in the long run. Subsidizing into unbounded pricing from incumbents will never solve the digital divide.”

Currently, the Oregon Broadband Office is contemplating how best to spend the nearly $700 million in federal broadband equity and deployment (BEAD) grants it’s poised to receive courtesy of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). The state’s 5 year action plan is due August 28, 2023, with a final proposal due in late 2024.

It’s hoped that this money can drive competition to market, though entrenched monopolies are working overtime to ensure the lion’s share of the funding goes to them, and not creative competitive alternatives.

Portland itself may not see much of this new BEAD funding. The program specifically prioritizes the deployment of unserved rural locations first, followed by underserved markets where users see speeds of less than 100 Mbps (megabits per second) downstream, 20 Mbps upstream. Still, there are a number of cities who have financed municipal network builds without relying on grant funding such as Fairlawn, Ohio and Hillsboro, Oregon.

Like many broadband reform activists, Senior is tired of waiting for federal regulators to tackle broadband competitiveness and high prices with any seriousness.

“The FCC could reclassify Internet access as a telecommunication service and enforce line sharing,” Senior suggested. “Or, even more laughably, the US Congress could pass new law that centers subscribers in telecommunication policy. Neither of these are likely, short of an astronomical event, like a random asteroid hitting DC. So, I have focused my energy on local solutions through public ownership of infrastructure.”

With an historic influx of federal subsidies and a major shake up of Portland’s political system, advocates for publicly-owned communications infrastructure see renewed opportunity to make affordable, accountable broadband access a genuine legislative priority.

Header image of Portland Riverbank courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

Inline image of Portland City Hall courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Inline Image of survey results courtesy of CTC Technology & Energy feasibility study

Inline image of Portland White Stag sign courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0)